The Day We Knew Was Coming Has Arrived

What the Fifth National Climate Assessment tells us about urgency and vision.

How bad is this planetary crisis? How bad will it get? What does its worsening demand of us? How do we see it clearly?

The just-released Fifth National Climate Assessment surveys climate progress and perils in the US. It offers an extremely useful overview of recent research on how well America is tackling the planetary crisis. This iteration does a better job than previous ones in getting at some of the more complex and unprecedented ways climate action, risks, and responses are changing — topics of central concern to this newsletter.

I took notes as I read it myself, and figured those would themselves be of some interest.

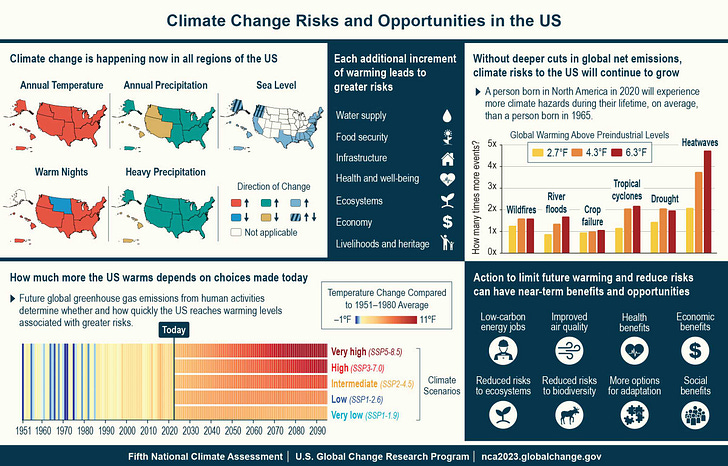

First, this very clear summary of the overall climate problem:

“The more the planet warms, the greater the impacts. Without rapid and deep reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, the risks of accelerating sea level rise, intensifying extreme weather, and other harmful climate impacts will continue to grow. Each additional increment of warming is expected to lead to more damage and greater economic losses compared to previous increments of warming, while the risk of catastrophic or unforeseen consequences also increases.”

While actions are being taken to reduce emissions — and have already created enough momentum to give us a very good chance to avoid the most catastrophic possibilities of the planetary crisis — we Americans are still, overall, failing1. Mostly, we’re failing by moving too slowly.

“While US greenhouse gas emissions are falling, the current rate of decline is not sufficient to meet national and international climate commitments and goals. US net greenhouse gas emissions remain substantial and would have to decline by more than 6% per year on average, reaching net-zero emissions around midcentury… by comparison, US greenhouse gas emissions decreased by less than 1% per year on average between 2005 and 2019.”

In other words, speed is everything, on climate and sustainability, but predatory delay and triangulation have limited us to moving far too slowly.

We have the potential to greatly accelerate innovation and uptake of solutions:

“Many cost-effective options that are feasible now have the potential to substantially reduce emissions over the next decade. Faster and more widespread deployment of renewable energy and other zero- and low-carbon energy options can accelerate the transition to a decarbonized economy…”

The depth of the changes needed, however, and the pace at which they must be deployed, mean we need to ratchet up to a more disruptive, wider scope of solutions, not just clean energy and electrification, but rapid changes in urban planning, transportation systems, building design (subjects I wrote about in my 2012 book, Carbon Zero); and in our food systems and our land management practices.

With bolder action, on fast timelines, we can still limit the further dangers this crisis will bring. But there’s no reversing the dangers we’ve already set in motion.

The crisis is already here, it’s already massive and its impacts on society are already a discontinuity, a situation never before experienced, indeed a situation in which our previous experiences and expertise offer little guidance.

“[T]he climate conditions and impacts people are experiencing today,” the report’s authors say, “are unprecedented for [at least] thousands of years.”

(The scale of the transformations already unfolding around us mean that an orderly transition is no longer possible: that is, our original strategy to rapidly limit warming to a level to which society could the affordably adapt without sacrificing any important continuities is no longer possible.)

Climate change is not an issue but an era.

All of the problems we face combine and worsen one another. “These interactions and interdependencies can lead to cascading impacts and sudden failures,” as the report’s authors say.

“Climate change is increasing the chances of multiple climate hazards occurring simultaneously or consecutively... Such interactions between multiple hazards across space or time, known as compound events, exacerbate the societal and ecosystem impacts of individual hazards and hinder the ability of communities… to respond and cope.”

(In addition, the planetary crisis brings not just climate change but also ecosystem collapse, biodiversity loss, resource depletion, toxics spreading through the biosphere and a host of other systems of humanity’s current unsustainability. Nor is climate change a singular problem, accelerating a bunch of various weather threats and eroding away the stability of human systems in a variety of ways.)

We are in now in a catastrophe of spreading brittleness and broken continuity that we can’t reverse or resolve, and that will not be made whole by any action within our power. There is no going back.

Of course, as the report reminds us, one of the salient realities of the planetary crisis is that “Climate change exacerbates inequities,” and that one of the gravest manifestation of climate inequity is both the growing number of climate refugees and the barriers facing their efforts to relocate (or emigrate).

In the future, the combination of climate change and other factors, such as housing affordability, is expected to increasingly affect migration patterns. More severe wildfires in California, increasing sea level rise in Florida, and more frequent flooding in Texas are expected to displace millions of people. Climate-driven economic changes abroad, including reductions in crop yields, are expected to increase the rate of emigration to the US… Displacements driven by climate change disrupt social networks, decrease housing security, and exacerbate grief, anxiety, and negative mental health outcomes.

(What the report doesn’t discuss is the likelihood that most (or all) of the proposed measures to safeguard the hundreds of millions of people at risk — to assist with disaster recovery or supported relocations in hard-hit communities, to compensate for loss and damage in the poorest parts of the world, to buy time for the developing world cities at greatest risk from climate destruction, or even simply to rapidly distribute clean technologies and technical expertise — will fall far short of what’s needed. The future looks increasingly transapocalyptic.)

The report offers blunt assessment of the failure of our attempts at adaptation: “current adaptation efforts and investments are insufficient to reduce today’s climate-related risks and keep pace with future changes in the climate.”

I’ve spoken and written quite a lot about my frustrations with the ways in which the language of adaptation and transition is employed to justify triangulated responses to risk: “In theory, adaptation and ruggedization discuss versions of the same thing,” I wrote. “In practice, adaptation too often means identifying discrete, predictable threats, ignoring others, and offering lowest-cost solutions for those risks that are easiest to anticipate — often becoming a form of triangulation, in which large future threats are acknowledged, but small, incremental steps as sufficient preparation for now. Adaptation often ends up meaning securing the unsustainable and brittle from change.”

There are signs that’s beginning to change. Some of what the report labels “transformative adaptation” gets at the kind of structural defenses, systemic innovations and focused growth we talk about as “ruggedization.” So, too, the broader definition of resilience the authors use (defined as “the ability to prepare for threats and hazards, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from adverse conditions and disruptions.”) gets at the need to respond to societal upheavals we’ve discussed before.

A host of other highlighted topics can be found in the report:

Homes and property are at risk from sea level rise and more intense extreme events. [See also, the brittleness bubble.]

Infrastructure and services are increasingly damaged and disrupted by extreme weather and sea level rise. [See also, The New Ruggedization Calculus: Build or Burn]

Damage to supply chain networks caused by climate change reverberates through people’s livelihoods and investments in ways that threaten quality of life and security. [See also, brittleness extends itself not just in geographies, but in networks and systems]

Many regional economies and livelihoods are threatened by damages to natural resources and intensifying extremes. [See also, The Personal Costs of Climate Chaos]

Climate change slows economic growth, while climate action presents opportunities. [See also, Seeing the future as full of possibility is seeing it clearly.]

Safe, reliable water supplies are threatened by flooding, drought, and sea level rise.

Disruptions to food systems are expected to increase. [See also, breadbasket collapse.]

Climate change exacerbates existing health challenges and creates new ones.

Ecosystems are undergoing transformational changes. [See also, The Great Return]

Continued warming could push some aspects of the Earth system past tipping points. [See also, We cannot act ‘too fast.’]

.

So, what are my take-aways? Three quick ones.

First, our ability to synthesize the science on (and clearly describe) the challenges and threats we face is improving. An average college-educated person might find the Fifth Assessment slow going and confusing in parts, but they could probably get through it and understand most of it. This is a win! (Thank you, climate communicators.)

Second, we who are active in shaping the public debate around climate change and the planetary crisis must find a better way to simultaneously both:

a) Acknowledge the agency humanity still has time to limit the crisis, to begin large-scale responses, and to protect those least able to protect themselves from the harms of discontinuity. It’s not too late. Indeed, we’re already doing a lot. We must do much more, but it’s time to stop acting like global societal collapse or even human extinction are likely outcomes now.

b) Admit the crisis has already grown terrible, even our best solutions are proving disruptive, and the scaling of society-wide collective action is stalled by the deep inertia in our politics and culture. Even if we do a lot more, we still can’t save everything, and we need to stop acting like saving everything and everyone is the measure of a successful approach. We are deep into triage now.

Third, the public debate still shies away from acknowledging our fundamental loss of continuity. Without that acknowledgment, we will remain unready for what’s already happened. We have a fierce need to see that we have gone through a discontinuity, and almost none of us are prepared for its amplification, for the ways in which discontinuities will grow and spread and interact.

We need new visions of what we’re trying to achieve — ones that embrace ambition and opportunity, but ground themselves on the limits and discontinuities created by the crisis we’ve already locked in.

This report is a step in that direction.

How to find me online:

- Schedule a consultation with me to discuss personal ruggedization in your life or business, or to explore a business opportunity.

- Hire me to give a keynote talk at your conference or a bespoke presentation. Email to inquire.

- Subscribers to this newsletter also get first notice about online classes (with subscriber-only discounts)

- Check out my books: Worldchanging and Carbon Zero

- View my TED Global talks on sustainability and cities.

- I was featured in a 2022 NY Times Magazine piece, "This Isn't the California I Married."

- I talk about personal ruggedization on these podcasts: The Big Story; Everybody In the Pool

- Visit my Bookshop shop to discover some of my top reads.

- Stay connected on social: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky

(Another just-released UN report tells us that American lack of progress is not exceptional, but rather the norm. Few nations are acting fast enough to avoid a dire worsening of the planetary crisis: “Even with increased efforts by some countries, the report shows much more action is needed now to bend the world’s emissions trajectory further downward and avoid the worst impacts of climate change.”)