The Transapocalyptic Now

It's not the end of the world, but it is the end of the world as we've known it.

A Story about when we aren’t

Of all the fairy tales that have blinded us to the realities of this new era, this is the most seductive — that the future ahead of us offers a simple, stark moral choice with a simple, stark outcome: we will rise to triumph and all will be well, or we will fall. Victory, or death!

In this just-so story, we get to cast ourselves as the heroes. Those of us fighting for climate action and ecological sanity are — against steep odds — the ones rescuing humanity (and all other living creatures). Our opponents are evil. The end of the story can only be our success, because for us to fail means the end of everything. (Man, there is no drug like self-righteousness.)

Central to the struggle, of course, is belief in continuity. That which was — or at least an idealized version of it, optimized perhaps to avoid some of history’s ubiquitous injustices — must be the future, as well. At the end of the fight, we come around, like T. S. Eliot, to “arrive where we started / and know the place for the first time.” After the struggle is won, there will be a homecoming.

But this is not a fairy tale. This is the world, and the world is not simple. The fight cannot be won and yet all is not lost. We are heroic only to the extent we mold ourselves into people who can succeed with purpose on a planet in permanent crisis. We live in discontinuity. We will live in discontinuity for the rest of our lives. It is our home now.

The Hidden Scale of Discontinuity

Nothing that we currently know how to do will roll discontinuity backwards and restore a new continuity. Reversal is a myth. Healing ecosystems, restoring the atmosphere, preserving biodiversity — all are critical efforts, but even in the sunniest scenarios, we will never find ourselves living again on the same version of this planet our ancestors called home.

Therefore, our world is full of largely irremediable unfairnesses. The scale of the pressures on communities around the world is quickly ratcheting up, and in many cases is already far beyond the capacities of even wealthy countries to lever down, meaning more and more of the world is becoming brittle in the face of the planetary crisis.

One of the consequences of having suffered five decades of predatory delay on sustainability and climate action is that all around the world many of our places — cities and coastlines, grazing lands and floodplain farms, mountain towns and fishing villages — are moving from a state of being able to cope with shifts in heat, rainfall, and natural systems to a state of depletion and worn-out incapacity. Worse is coming.

Strains on our systems are increasing. Larger and larger hurricanes, higher floods, hotter heatwaves, megafires large enough to create their own weather: sudden and massive destruction is becoming more common as the planet warms and the crisis worsens. The longer we delay climate action — and the less lucky we are as the various parts of the planetary crisis combine and intensify — the more chaos we’ll experience, and the less our current systems of buffering people against danger (by, for example, providing insurance or offering rebuilding relief) will be able to function. Big weather should scare us.

But it’s the more subtle changes — the slower, deeper transformations — that should really rivet our attention to the planetary crisis.

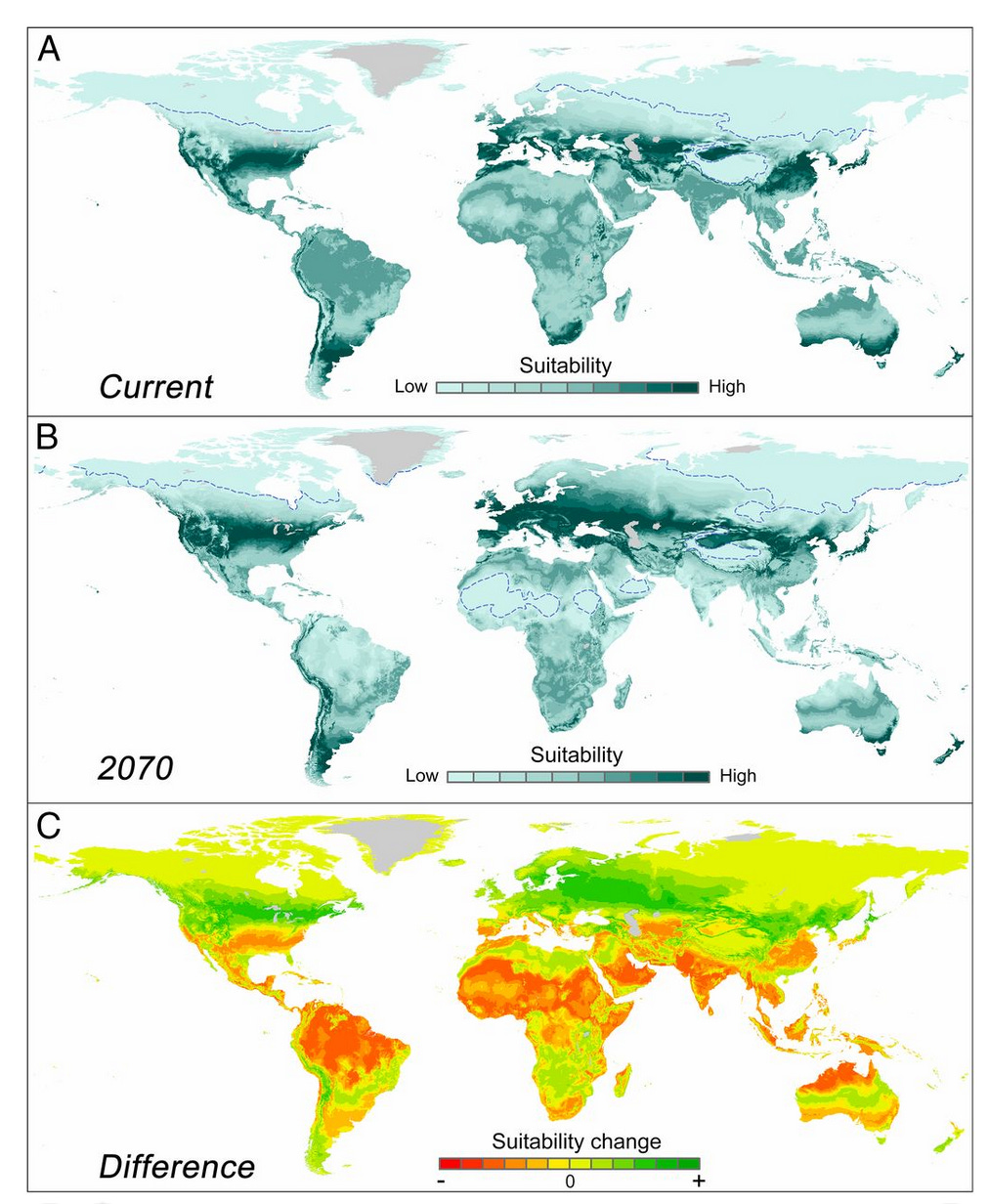

In every corner of the Earth, conditions we’ve long taken for granted no longer exist, and slowly and surely other sets of conditions are taking their place. What grows where and how well, the progression of the seasons, what dangers can be safely ignored and which demand our vigilance, how we must build our homes and plan our cities, whether or not we can rely on the infrastructure and supply chains our communities depend on for their very existence, even how stable our societies themselves are: all of this is in flux around us now. Past experience of place has become at best an imperfect guide to that place’s emerging realities. None of us are at home in the way we once were.

These transformations portend enormous hardships. Despite the claim that a few places are benefitting more than they’re losing (like Arctic ports in Russia), the reality is that the physical changes brought on by the confluence of global warming, ecological decline, resource depletion and toxic pollution will cost most of us severely. Sure, we’ll be paying in lost prosperity when the derecho winds slam through the plains, or when a cold snap plunges a state into darkness, or when a novel bat virus becomes a global pandemic. Even more though, we’ll all be suffering constant bleeds of resources: when the cost of food goes up as droughts deepen, or when water gets rationed, or even (as we’re seeing now on the West Coast) when we have to buy air conditioners and purifiers to make it through what were always sunny, clear summers, but now can be blisteringly hot months choked with smoke. Almost all the direct consequences of planetary change take from us, and give us very little back.

That isn’t to say that there’s nothing to be done about that situation. Most of my work focuses on the ways in which responding to the crisis with disruptive speed and applied innovation can empower us to build new systems and institutions and practices — ones that unlock opportunity within this crisis. We can create sustainable prosperity. We can ruggedize. We can learn to plan and act dynamically in a rough and unpredictable world. If we fight hard enough and move fast enough, most people can even come out of this process better off then we are now.

That’s a big “if,” though. Indeed, with progress halting at best in the U.S. and elsewhere, and the firmness of the pledges and commitments of the COP 26 conference far from assured, it’s a freaking Sasquatch of an “if.” Each of us has to decide how much confidence we want to place on that planetary conditional.

There are two more Sasquatches in the room, though. The first is that it takes resources to seize the opportunities of the Snap Forward, and wealth inequality is one of the defining realities of the human experience, today. The second is that not all places (and systems and societies) are equally provided with the material bases for making progress.

And while we can improve the stability of some places, we aren’t really doing much of that very fast. Meanwhile, the demand for stable places is growing far, far faster than most of our debate wishes to acknowledge. Hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of people need a stability they do not have and cannot build.

The Injustice of Delay

Discontinuity falls heaviest on those with the least.

The less wealth a community has, in general, the more the members of that community are dependent on the bounty of nature that they can access themselves — especially when it comes to growing food, securing water, making shelters, and so on. In past times, this wisdom was an incredible toolchest of strategies for survival. But place-based wisdom loses its edge when a place goes through unprecedented shifts into instability.

In addition, whatever talents and skills the members of that community may possess, poorer communities have fewer resources with which to make the kind of big investments that adapting to new conditions may demand of them, even when those new realities take hold only slowly. It takes more than hard work. It takes money, and the legacies of underdevelopment, colonialism and corruption often combine to make money very scarce.

Still, where discontinuity erodes away the reliability of the physical systems upon which communities depend, people must act. They have to do something to save themselves.

We know from millennia of history that poor people forced into more desperate circumstances tend to fall back on the same few strategies. One is to deplete future resources in order to survive present challenges (the proverbial eating of the seed corn; cooking next year’s crop to make it through a tough winter). Another is conflict, seizing resources from others who have them. The third is to try to move to somewhere else where life may be easier (remember, for instance, the American Dust Bowl).

The combination of crisis and desperation, of course, produces all sorts of horrible repercussions: civil wars, epidemics, mass-migrations, economic collapses, cultural breakdowns, and all the rest of it. Where all of this mixes together, and gets worsened through geopolitical power plays and exploitation, the results can be what most people reading this would consider apocalyptic.

The planetary crisis means a huge increase in the number of people who will be pushed up to the very edge of apocalypse. Many will be driven over. This is an unjust price they will pay for decades of predatory delay by slow interests. We often hear of the externalities of oil or logging or toxic industries: the cooking fires of refugee camps are where we can see them most clearly.

The wealthy world can and should do much more to help, beginning with fierce and focused action to prevent this discontinuity from deepening more than it must. In the context of climate and sustainability, speed is justice. All is not lost.

From everything I’ve heard and read, though, no one studying these problems seriously expects them to get anything less than much worse. Through our inaction, we have set in motion a whole series of local and regional apocalypses, even if some of them are still decades away. Much of the world is being rendered less habitable.

The 21st century will be apocalyptic… but not everywhere, and not for everyone. And we are far from helpless.

Our transapocalyptic world

To act with smarts and guts in the face of the planetary crisis, we need to get real about what failure actually means.

First of all, failure does not mean the End of the World. One of the problems of believing in binary climate futures — we either seize the chance to take climate actions that will supposedly restore continuity, or we plunge headlong into extinction — is that it facilitates well-off people ignoring the realities of poor people by turning their very real and particular catastrophes into mere b-roll examples of End of Everything. It takes actual people’s challenges and makes them only an illustration of the horrible fate stealing over us all. They can’t be helped, and we are powerless in the face of the collapse — which is privileged crap. Indeed, it takes a lot of unquestioned privilege to feast oneself on the luxury of despair, while turning others’ lives into anecdotes of doom to be told at dinner parties.

Even if we continue to really frack up climate and ecological action in the short run, massive action is now inevitable. Our great-grandkids are not going to be hunting alligators through Arctic swamps. It is not too late for us, or for them, and the odds are running more and more strongly against the very worst outcomes we once imagined. The scope of possible impacts is vast, and the scale of risk is difficult to comprehend, but there is a very, very, very long distance between the kinds of disasters we know we’ve already set in motion, and humanity being scoured from the face of the Earth.

Second, unjust as it may be, the consequences of failure will fall more lightly on some than others. We live amidst vast wealth and unprecedented capacities. While no place is safe (if by “safe” we mean unlikely to suffer consequences), many places can be made relatively durable in the face of changes in the climate and biosphere. Some places, at least, are already trying to ruggedize themselves and make the need to change into an opportunity to thrive. There are pathways to sustainable prosperity that also deliver the ability to bring much larger resources to bear in minimizing the dangers communities face.

We live, today, in a world where some people worry about their family surviving the trip to the next source of water, and others fret over having to buy their second-favorite brand of coffee. We will live in a world with equal (or even greater) chasms of fortune in 20 or 30 or 40 years.

I call this reality a transapocalypse. A transapocalypse is a spectrum. Some parts of the world will experience death and suffering and tragic upheavals as horrible as any humanity ever seen, even while others experience unprecedented prosperity. This is already the nature of the world, and one of the worst things about this planetary crisis — this once-avoidable ecological tragedy that will chew through our world for generations to come — is that its transapocalyptic nature is now baked into its future. In the real world, we will be doing extraordinarily well over the coming decades if we can limit the number of people who wind up living in apocalyptic conditions to a merely vast number — say, tens of millions.

Doing that will require acting fast to limit the planetary crisis. It will demand quickly lowering the costs of new systems and practices that deliver people’s needs with a fraction of the planetary price, then scaling them up at breakneck speeds to work for billions of people. It will demand smart policies, more effective politics, fairer rules for finance and trade, and some stunning diplomatic successes. Such successes are possible.

But it will also require something more: it will require ruggedization on a scale we’ve not yet really even imagined. It will require not only lessening the transapocalyptic pressures bearing down on humanity, but greatly increasing the number of places and systems and institutions that are capable of thriving in a much more discontinuous reality.

Right now, there are more and more people finding themselves compelled to make moves, often geographic ones, to get themselves and their families better odds. This is not just true of those millions for whom relocation is survival. Even in the wealthiest countries, more and more people see that even if the future of their community is not apocalyptic, it is visibly degrading as changes erode away the material basis of its comfort and security. More of us are in this situation than any of us like to think. We are each of us on the transapocalyptic spectrum, even if we are still a long way from the bottom. Ask not for whom the warning klaxon blares.

The Bottleneck

For all the millions of people finding themselves pulled into apocalyptic situations, there are also millions of people living high and dry and pulling in greater and greater returns on their investments. Many are already reacting to the upheaval around them with lifeboat thinking — seizing what they sense will be needed and limiting access to it for their own benefit.

We increasingly live in a world of refugee camps and luxury survival compounds. There is a boom in private security services, private fire services, independent medical care, the ability to use investment commitments to buy multiple passports to give you a bolt-hole somewhere like New Zealand, Malta or Switzerland — a vast industry rising to provide private protection, for the wealthy, from the impacts of the planetary crisis.

At the same time, there is a climate-savvy gold rush beginning, where well-resourced people are looking to buy up the things that will be working and thus valuable in a transapocalyptic world — and get as many of them as they can before people realize how valuable those things are. Think speculative investments in assets like farmland, water rights, rare minerals, fishing rights, and real estate in better-sheltered cities.

Essentially, they’re arbitraging misery. They’re taking advantage of a widespread lack of understanding of the tempo of change to create zero-sum fortunes where their benefit comes directly from the inability of others (who find themselves under transapocalyptic pressures) to access other alternatives. They’re banking on a mixture of scarcity and desperation for big payouts. In a very real way, they’re hoarding the future.

The result is a bottleneck. That is, there are many more people who need homes in ruggedized places, access to resilient natural systems, and participation in equitable and dynamic economies than there are homes, healthy places or good opportunities to be had. Currently, the mismatch is of a staggering magnitude.

The Boom

That bottleneck, though, is more a matter of choice than of supply. We can, right now, choose a much different future. We can choose to build. We can make more future instead of hoarding it.

All good climate futures now involve an absolutely gargantuan amount of new building and major infrastructure investments. Indeed, a giant building boom is what successful climate and ecological action looks like on the ground.

We’re rightly concerned about the scale of deployment of clean energy supply, energy storage, energy efficiency technologies and demand-reduction plans and policies that are demanded to decarbonize the world’s energy supply. But low-carbon energy is only one part of the job we face; there are also emissions challenges with agriculture, methane, deforestation, chemicals, and so on. Bringing our civilization into balance with the carbon cycle is a epochal undertaking, and involves essentially rebuilding the world’s industries, even while we scale them up.

Ruggedizing ourselves will be a bigger — and no less pressing — task than cutting CO2.

Just catching up is a massive challenge. We must rebuild all the degraded systems around us, work our way out of technical debt and deferred maintenance, and build our way out of the current housing shortage, which is at least hundreds of millions of homes.

We need simultaneously to upgrade that whole process to accomodate our new realities. Engage in climate triage, and abandon all that is untenably brittle. Ruggedize our utilities and transportation grids and cities and everything else to thrive in a much wider range of circumstances than we’re used to expecting. Prepare to accommodate millions of new refugees and welcoming even more internal climate migrants. Speed is justice, and scale is inclusion.

Finally, we need an intellectual and creative leap into engagement with the realities of our transapocalyptic present. If we are not foolish, we will be learning more, listening more, helping more, sharing more, engaging more and, unfortunately, intervening more. Because on a small planet, no one else’s crisis is theirs alone. Denial is a flimsy wall, and border walls and sea walls will not prove much stronger. Connection is the only effective strategy.

The transapocalyptic may feel distant, but it’s already here.

If you found this letter interesting, please share it on social media or send it to a friend or colleague by using this button:

If you’d like to read more (or listen to the private podcast for paying supporters), please subscribe:

Thank you!