Ruggedize Your Life.

Why smart choices about where and how you live are the key to surviving and thriving in a planetary crisis.

UPDATE: If you are interested in taking my intensive personal climate strategy workshop, it will be be held in January 2026.

You can sign up here to be notified, read a review of my course, or go to my climate foresight guide to find out more about the work I do and what I teach.

"Upterrlainarluta.” Yup'ik, VERB: “to be wise in preparing for the unknowable."*

PLACE IS THE KEY TO PREPAREDNESS

When it comes to the planetary crisis, the most important question you can ask yourself is “Where?”

It feels almost anachronistic to say it — in these days of globalization, international entertainment, worldwide travel, remote work, constant connection and instant access to everything — but the most important choice facing you and your family as the planetary crisis crashes down is where you choose to be. Where you live, and even more, where you have the right to live, will bound and determine your options when shit gets real.

How do we get smarter about making that choice?

HOW DOES THIS CRISIS THREATEN US?

We must begin by understanding the nature of the crisis we’re in now.

We live in a time when every major natural system is changing faster than it has since modern humans like us have walked the Earth — and many of those changes are getting worse at increasing rates. Effectively none of these changes are good, and many threaten our homes and livelihoods.

The most obvious danger we face in out lives is of sudden disaster: storm, flood, fire. Even in the best case, even when no one we love is hurt and our material losses are insured (which is less and less certain to be the case), being wiped out — being forced to flee with your family, your pets, your go bags and as many treasured possessions (like photo books and heirlooms) as your car can hold — is a traumatizing set-back in life. There’s a reason we speak of disaster victims. Doing your best to avoid tragedy is smart.

But you don’t have to be in the wiped out to have your life overturned. That’s because each of us is dependent on a vast web of systems and services that make our lives work. Serious, repeated blows to those support networks can cause real, long-term losses. When the power grid fails, when the railroads wash out, when supply chains break down, when the public health system can’t keep up with novel viruses, when the asphalt on the streets melt in the heat, when water gets rationed because of drought: all of these undermine our prosperity, and — added together and happening more frequently — they can, as we’ll see, impoverish and immiserate whole regions.

This planetary crisis is a discontinuity: that is, it renders current expertise and past experience poor guides to future decisions. Knowledge that we have set in motion these kinds of impacts — and others we can’t yet foresee — itself is a huge impact. It forces new calculations of risk and advantage through our politics and economy, leading to upheavals that unfold even more quickly in the human world than nature. Even though impacts will certainly worsen over the coming decades, the planetary crisis is not a future problem. We’re living in it, now.

WHAT IS “SAFE” IN A PLANETARY CRISIS?

There are no safe predictions, now, only good accountings of the odds we face.

If you had asked me 10 years ago what places would likely be relatively safe bets for climate durability, I’d have definitely included the American Pacific Northwest and Western Canada on my list.

Yet, as I write this, Vancouver and British Columbia are living discontinuity. In the past two years, Vancouver/BC have experienced a zoonotic pandemic; a savage heat dome; record megafires and (for a time) the worst air pollution of any major city anywhere in the world; and an atmospheric river, with record rainfalls, catastrophic flooding and infrastructure collapse that has temporarily cut Vancouver off from the rest of Canada.

The thing is, I wouldn’t have been wrong to say Vancouver’s a good bet. Its odds were good. But sometimes you lose even good bets. The dice roll and the improbable rears its head.

The other thing is, Vancouver is probably still a pretty good bet, compared to many places in the world. That’s because, first, what happened there over the last two years was unlikely, and the odds are decent that it won’t quickly be repeated. But second, and more importantly, British Columbians have the power and resources to respond to their changing circumstances.

No place on Earth will escape climate and ecological upheaval — no place is, in that sense, safe. But some threats are not as grave as others. Some dangers are muffled by geography and historical advantage. Some governments and economies are better prepared than others. Some places are better able to manage in the face of discontinuity. Being totally safe is not an available option. Being safer than you’d be elsewhere and being more able to cope with crisis is — that is an option that still exists, in places.

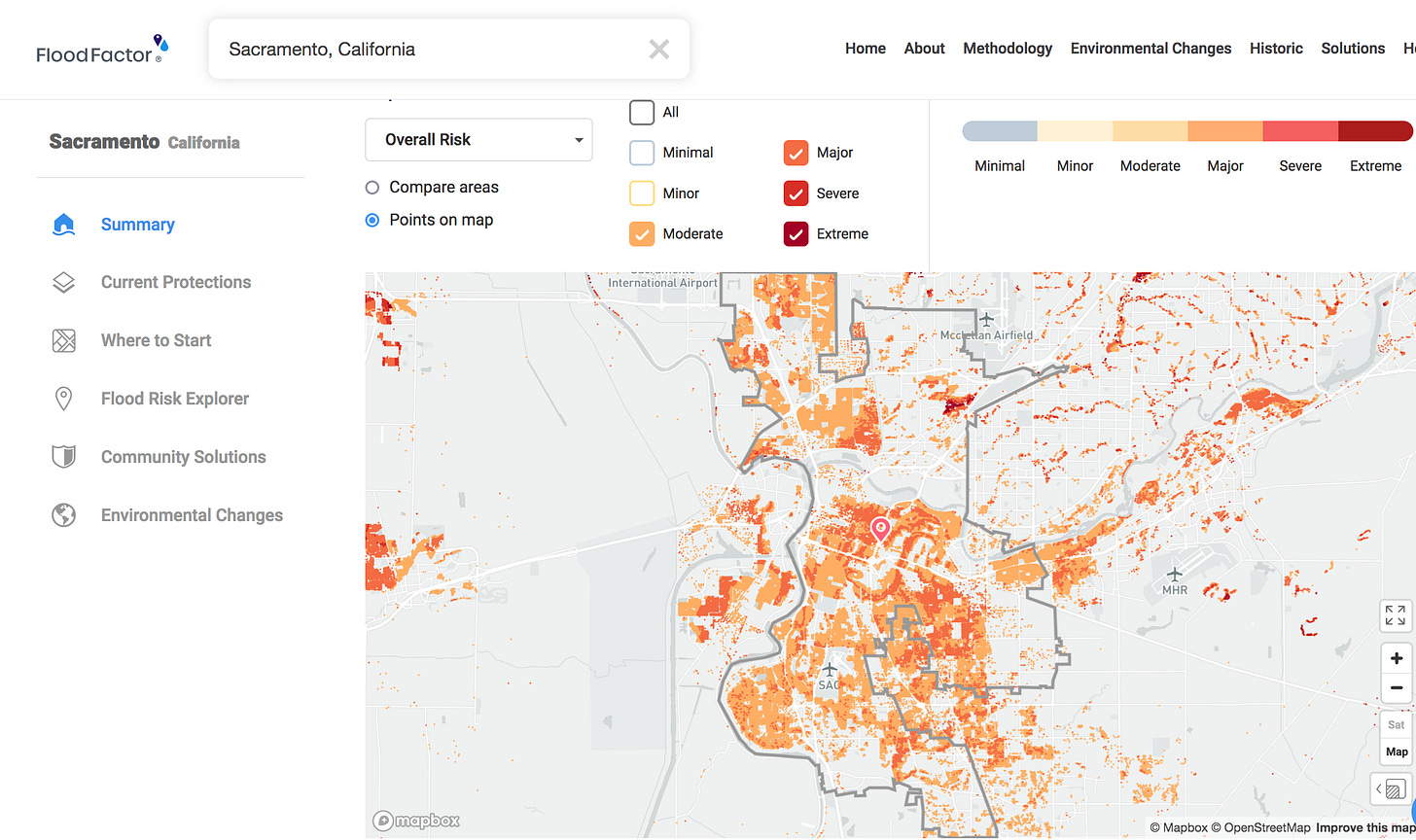

Mostly this is a process of elimination: discard from consideration the places with severe risks, or multiple overlapping risks, and take a closer look at what’s left. It’s pretty hard to say with any confidence that place X is safer than place Y. It is, though, increasingly easy to identify places that are simply unsafe. Is it likely to flood? Will it likely be dangerously hot? Is it surrounded by flamable forests? Is it at sea level, and in a stormy part of the world? Absence of risk is hard to show, but deal-breaking risks are more and more plain to see.

My next piece in this series explores this question in greater depth, so I won’t say much more here, except to say that putting in the effort demanded to figure out how to avoid clear and dire risks is a necessary first step in choosing wisely.

A WIDER LANDSCAPE OF LOSS

The consequence of choosing poorly (or being unable to choose) is to find yourself facing the future in a brittle place. As the planetary crisis deepens, more and more places will become brittle. It’s a “widening bullseye.”

Everything people build is built with tolerances in mind. Part of living in a place is having a good sense of what is normal for that place, things like how much rain falls, how cold it gets in the winter, how often the ground shakes in an earthquake. You don’t see a lot of roofs in the desert that are pitched to hold six feet of snow; you don’t find a lot of air conditioners in northern seaside cities.

Larger systems are built with tolerances in mind as well. Bridges are designed to withstand hundred-year floods, but not built to be safe if a once-in-a-thousand-year flood comes. Powerlines can take high winds, but not category five hurricanes. Supermarkets can keep the shelves stocked if deliveries don’t come for a day or two, but if the trucks stop running for a week, most stores shelves will be bare.

As we make the world hotter and less ecologically stable, events more and more frequently overrun the tolerances for which our world was designed. The thousand-year flood hits three years in a decade; powerlines go down every storm season; people go hungry when an unprecedented spring blizzard dumps four feet of snow in a weekend. Each of these events causes damage, often a lot. According to NOAA, over the last decade, major U.S. disasters alone cost “at least $890 billion from 135 separate billion-dollar events,” with trillions more lost in smaller disasters and unseasonal disturbances. Everyone informed expects that worse is on its way.

Places that are exposed to regular exceedance of built tolerances — and thus that are at risk of failing catastrophically — are brittle places. It is possible to take a climate-vulnerable situation and work systematically to reduce its vulnerabilities — as the continued existence of the Netherlands proves. But it takes time, and money.

Around the world, nothing like the needed resources being spent to make safer the places that can to some degree adapt. Many places even here in America that could be doing better are simply drifting towards the next disaster, and no place of which I’m aware is yet doing enough to prepare, fast enough to be ready.

As the severity of the risks we face becomes clearer and clearer, resources will start to flow. More money will be spent, but not everywhere. Indeed, understanding where the money likely won’t get spent could be the difference between building a plan to thrive and struggling to survive.

Here’s an important thing to know: exposed regions are not just less safe for you, personally, they’re also at an increasing economic disadvantage. Those economic disadvantages can be crippling to your hopes, even if the particular place you’re in manages to dodge every bullet climate chaos sends flying at it.

Risk itself, you see, is increasingly a source of loss. As awareness of risk grows, the financial value of risky places drops. Where meeting that risk is more expensive than decision-makers think a place is worth, it simply won’t be defended. It will be unofficially abandoned. That will then create more problems. Bonds for big projects, loans and mortgages, business investment, insurance, talented workers — all will grow more scarce. Then, value will crash, a phenomenon I call the Brittleness Bubble.

This also helps explain why so much work on prepping and living off the grid is less effective than we’d like it to be. You can improve your immediate surroundings, but if you’re surrounded by a landscape of loss and broken systems, you’re still in for a bunch of tough years.

Preparing is smart, wherever you live. Deluding yourself into believing that any amount of preparation most people are prepared to do on the budgets they have will make them immune from the misfortunes of the society around them is dangerous. (I have a podcast coming on the difference between the two…)

WHAT IS RUGGEDIZATION?

Ruggedization is a term I borrowed from the military. I use it describe the process of turning the need to make systems durable (in the face of unprecedented and often unforeseeable threats) into a force for transformation. That means designing responses that can mobilize the resources needed for rapid, large-scale change by making those approaches powerful opportunities rather than just protective investments.

As things fall apart, places that want to avoid falling apart with them will have to take bolder, faster actions. Ruggedization protects the system or place by building new systems to prepare it for a wider range of future conditions.

Meanwhile, the combination of protected current value and new value created in the process means not only more local prosperity, but a better ability to borrow money for government services and infrastructure, attract capital for local businesses, insure people’s homes and workplaces, and draw in talented and energetic people. Ruggedization increases access to resources, meaning more capacity to withstand difficult times, and more opportunity to increase the scale of future efforts, benefiting more people. (I’ll be talking more about why scale is inclusion in an upcoming podcast).

WHAT IS PERSONAL RUGGEDIZATION?

“We’re all in this together,” we often hear said about the planetary crisis.

This is demonstrably untrue. We should be coming together, but the opposite is the case…. The planetary crisis itself is rooted in conflict over the pace of change, with pressing ecological concerns pitting those who profit from predatory delay against the many who benefit from bolder action. Climate politics are the politics of tempo. They are as divisive as politics come: they grow more zero sum (more we-win-you-lose), every day bold action is delayed. So, no, we’re not all in this together.

It’s a little more hardcore than that, though: we are in the grips of a massive discontinuity, and even if we could gain agreement on widespread collective action on a rapid pace, we’ve already locked in a massive amount of mayhem.

There is no plan to make sure everyone comes out of this okay… no such plan may be realistically possible, now. You can’t assume that someone is taking care of all this for you, that help is on its way, that the boss has you covered. You (and the people you love best) have to be your own best advocates, and whatever your ambitions and values are, that means strengthening your own situation. Just as discontinuity is the job when it comes to our professional lives, ruggedization is the key when it comes to our home lives. (Indeed, the two are connected.*) The levees are about to fail, and chances are you’re not yet on high ground.

So, what does high ground look like?

We all rely on systems to make our lives possible. Getting to high ground demands finding places that are comparatively safer, that have already made choices in their planning and investments that don’t disadvantage them too much in a more chaotic world — and, above all else, that show a willingness to change quickly, to ruggedize further. Speed is strength in these times.

High ground means a platform for action, for rapid personal ruggedization at home, and the chance to accelerate larger-scale ruggedization in the community, systems and institutions around you. Unless you can afford to simply buy your way out of the crisis, personal ruggedization is the only smart strategy.

CAN YOU AFFORD TO BUY YOUR WAY OUT OF THE CRISIS?

Like so many things in our world, access to climate safety is increasingly allocated by wealth.

Most of us understand this to some extent. The divides, though, between the haves and the rest are much wider than most of us feel good about admitting. In a world where many people walk, bike or take informal transit, being able to expense business class travel demonstrates some serious advantages — but it doesn’t put you in the same league as folks who own their own Learjets.

If you’re very rich you can simply have a more stable future delivered to you. In fact, you can create a system of supports around yourself sufficient to see you through even fairly severe long-term problems.

Luxury survival compounds. (It’s worth knowing that though our idea of a survival compound location is often a remote island or vast ranch, many compounds around the world exist within cities’ metro regions, where access to the luxuries of life and the centers of power are close. I suspect that’s the real growth market for these things.)

They’re protected by private security and imposing barriers — physical walls, the visible availabity of armed response, deterrent designs — giving them the ability keep people out. They’ve retained private firefighting and rescue services. They’ve secured conceirge access to private medical facilities, and have the ability to help build those facilities wherever they’re needed. They have hardened homes (or “resilient estates”) built to easily weather most common disasters, as well as food stores, off-grid water, energy and waste systems. They have sturdy communications infrastructure. And, if all that fails, they have other homes elsewhere, and extranational bolt holes in places like Switzerland and New Zealand.

The richer you are, the more redundant private systems you can afford to layer over the public civilizational support systems around you. If you’re very rich — say you have a net worth of $25 million or more — ruggedization is simply another investment criterion, and, if you make smart decisions, it’s not even much of a risk, given expected gains in value. It is extremely expensive to buy in, though. The number of people in the entire world who are that rich is likely a million people or less (in the U.S. it’s roughly 200,000 households).

Most of us can’t afford to maintain a personal backup civilization in case the one we’re depending on goes down for a while. Even among those of us doing pretty well in the wealthy parts and pockets of the world, the overwhelming majority of us can’t afford ruggdeization-through-redundency. We have to commit to a community. We have to place a bet on a place to live.

Many good people will lose the bets they place, especially because many people’s only available bet is to stay put and wait and hope.

MANY PEOPLE CAN’T AFFORD TO RUGGEDIZE

The planetary crisis is not an issue, but an era — and to live in this era is to experience what I call its transapocalyptic nature.

Every person on Earth is now experiencing climate chaos and ecological disruption. This will only increase, no matter what we now do (though we’d be wise to act as boldly as possible to minimize that increase). Stabilities we’ve taken for granted are falling apart, at a faster and faster rate.

This isn’t good news for anyone. But it is much worse news for some people than for others. We’re already seeing vast differences between the fates that befall us as catastrophes spread — and those fates are, to a large extent, decided by the accident of where you happened to be born.

As I wrote in The Transapocalyptic Now,

“Discontinuity falls heaviest on those with the least.

“The less wealth a community has, in general, the more the members of that community are dependent on the bounty of nature that they can access themselves — especially when it comes to growing food, securing water, making shelters, and so on. In past times, this wisdom was an incredible toolchest of strategies for survival. But place-based wisdom loses its edge when a place goes through unprecedented shifts into instability.

“In addition, whatever talents and skills the members of that community may possess, poorer communities have fewer resources with which to make the kind of big investments that adapting to new conditions may demand of them, even when those new realities take hold only slowly. It takes more than hard work. It takes money, and the legacies of underdevelopment, colonialism and corruption often combine to make money very scarce.

“Still, where discontinuity erodes away the reliability of the physical systems upon which communities depend, people must act. They have to do something to save themselves.

“We know from millennia of history that poor people forced into more desperate circumstances tend to fall back on the same few strategies. One is to deplete future resources in order to survive present challenges (the proverbial eating of the seed corn; cooking next year’s crop to make it through a tough winter). Another is conflict, seizing resources from others who have them. The third is to try to move to somewhere else where life may be easier (remember, for instance, the American Dust Bowl).”

Hundreds of millions of people in the poorer parts of the world live in vulnerable places, yet have effectively no way of ruggedizing their lives, at all. They may be experts at adaptation and survival, but they do not have the resources to make effective choices about how to derisk their futures. If we delay action on the planetary crisis too long, the number of people living in transapocalyptic realities could end up in the billions.

The worse things get, the more transapocalyptic realities will take hold in the world’s richer countries.

THE RUGGEDIZATION BOTTLENECK

Transapocalyptic realities are coming to the wealthy world because we’re simply not doing enough to prevent them. There is a massive gulf between the number of people who need safer, more rugged places to live and the number of those places that exist or are currently being created.

Wealthy nations could act. They could combine huge investments to rebuild and ruggedize as many places as possible. They could create plans and policies for “managed retreat” on a massive scale, with generous support designed to help those most hurt to land on their feet elsewhere. In most places in the world, this conversation has barely begun. No one’s doing it, but many countries and regions could.

That would take money, though, real money, certainly more money than this country has ever spent on anything but war. It's becoming obvious that making an America where there's a rugged, secure, prosperous place for every American would demand a scale of change literally no one in American political life is even entertaining... or possibly even imagining.

The idea that increased concern for community “resilience” will make things better in truly brittle places, even in the short run, is wishful thinking. Just as some enterprises, institutions and communities “triangulate” their climate strategies — declaring lofty long-term goals, taking some small, unchallenging steps, then spinning those steps as evidence of commitment to those distant targets — the idea of climate resilience can be used to triangulate statements of resolute support for frontline communities with relatively paltry investments.

Triangulation strategies exist not to change corporate priorities but to protect them from change. So, too, with triangualted resilience. Giving community groups small grants, funding a few school retrofits or community gardens or small infrastructure upgrades, and providing token representation in critical debates about the future — these cheap moves can make unofficial abandonment sound like empowerment. That keeps the pressure off our leaders.

People need large-scale help. Working-and middle-class Americans are moving less often and over shorter distances; social mobility has effectively begun to reverse itself here (though it’s not doing great anywhere). Most people who stay put through the trouble will find themselves worse off in a whole tangle of ways, and there’s a very good chance that drop in their fortunes will impact their children and grandchildren, too. If you’re not doing well now, ruggedizing becomes even more important; if you live in a deeply brittle place, relocating is the only real option.

The blunt truth is a lot of people will not be making the journey to places where their future could be made more stable. Way too many places will slide into instability as people understand just how high the high water mark can rise, and values crash. No one’s coming to save those who end up abandoned in the ruins of the unsustainable*

Here in America, it’s tempting to hope for political movements on a grand scale. Because we’re drifting into an American future that’s profoundly unfair, many of us want to believe that as things get worse, this nation will be forced into an era of radical social change — that injustice will trigger the movements needed to reverse it.

Unfortunately, that’s just not a given. Few forces around us point to the recovery of the middle class, much less the widespread enfranchisement of the poor — and climate stresses don’t seem likely to change that. Heck, we live in a country where poor people already drive an hour-and-a-half from their uninsurable homes in underserved floodplain neighborhoods, through stifling smoke and heat, to staff restaurants and hospitals, and clean the homes and landscape the yards of wealthy people living comfortably above the waterline, in tree-shaded, safe communities with newly ugraded infrastructure. That’s now.

When I say that this stupid and preventable tragedy pisses me off — well, if that were any more of an understatement, it would just become a long pause. But this letter is not about raging against what’s gone wrong, this letter is about how to make sure that each of our lives have the best possible chance of going right. Awaiting The Revolution is not much of a personal ruggedization plan.

For a bunch of us, personal ruggedization means moving. We should be thankful that we have that option. But we need to work to understand the dynamics we face. Those with enough advantages to be able to take action, but without the resources to simply buy safety, must pay attention, must learn how to see what’s happened, because no one else is coming to save us. This, obviously, includes many young people in wealthier parts of the world. And time is short.

One of the great unfairnesses of our world is that many of the places best positioned to endure what’s coming are in the nations most responsible for the planetary crisis that has overtaken us. The ability to combine wealth, natural advantages and expert preparation makes rich countries more rugged countries, if they are led with any competance (a big if here in America).

Nationality can mean safety. Transapocalyptic circumstances are not stopped at borders, of course, but people often are. Access to more stable, better prepared and wealthier places is — already now and almost certainly more so in the future — limited by access, by residency, by citizenship. You cannot save yourself by moving if the place you need to move to won’t let you in. In the next few decades, huge numbers of people will inevitably flee transapocalyptic situations, only to find themselves trapped in only slightly better conditions.

But you don’t have to be poor or even from a poor country to feel trapped against a bottleneck. Even if you live in a wealthy part of the world, and have the smarts and foresight to be ready to relocate, you may find it hard. That’s because if you’re young, or from a modest background, or have experienced misfortune, or work in an under-compensated field (like teaching, social work or the arts), you face a barrier large enough to feel like a border: cost.

THE PLACES THAT ARE ALREADY IN THE BEST SHAPE ARE EXPENSIVE

The biggest barrier to moving to a safer place is often the cost of buying in.

Many places safer from harm are already wealthier than their surroundings. Mostly, this is because comfortable people in the past weren’t stupid, and tried to build in places with nice views and few problems. You don’t find a lot of historic mansions built on the river bottom or on an unstable slope.

It’s also because the word is out — it’s been out for a while — and smart people with the means to choose have already been sorting themselves into the places they think have better prospects. You can, today, go on the real estate site Redfin and get a rough assessment of the climate risks facing a given property. While these gauges are of necessity pretty rough measurements, the fact they’re offered at all tells you many people value climate durability now. People who are well-off enough not to sweat a big mortgage but not rich enough to build themselves a compound are trying to figure out what places offer good futures today.

Three attributes tend to define these places.

The first is simply a relative degree of safety. They’re not directly in the crosshairs of the most likely catastrophes.

The second is good bones. When it comes to ruggedization, urbanism is an advantage. As designer Matt Jones wrote, a “city is a battlesuit for surviving the future.” The more compact, walkable, and well-provided with working infrastructure and institutions a place is, the more protection it offers.

Concentrated value also makes upgrades to infrastructure more cost-effective — increasing the odds that further funding will be available. Denser, lower-carbon living protects from the economic shocks we can expect as unsustainable industries are priced more realistically and action becomes more disruptive to incumbents.

The third is rich neighbors. Wealth alone will not make a sprawling, brittle place safe. But in places that are less brittle, with concentrated value, wealth leverages the capacity for on-going changes that will keep these communities ruggedizing.

Wealthy places have more power: they have larger tax bases; they’re home to philanthropic donors; residents have more ability to create islands of stability, with more families having the resources to prepare, and homes increasingly including passive survivability measures; a concentration of experts and executives means more ability to draw outside public funds, talent, and capital investment — and networks that can secure large-scale advantages and forge disproportionately powerful booster networks.

Unfair as it is, wealthy cities and neighborhoods with natural advantages are better platforms for personal ruggedization. The old advice that it’s smart to buy the smallest house in the best neighborhood you can afford is probably tripply true today. The problem is, you often have to be pretty wealthy to purchase even the smallest homes there now. Even those of us who are doing pretty well face real challenges when we think about how we can help our kids (or our parents) get established in the kind of places we’d like to see them have access to.

HOARDING THE FUTURE

When we’re trying to make smart decisions in our own lives, it can help to think of the bottleneck as an invisible housing shortage.

We all know that there’s a massive global housing shortage, and a huge shortfall in the U.S.. We all know home prices are rising astronomically. Here in California, the Legislative Analyst's Office pegs the shortfall at more than 3 million homes, while Senator Scott Wiener, the state Senate’s leading housing expert, estimates the shortage to be at least 4 million homes.

But even these numbers are misleading. Because much of the existing housing stock is in vulnerable or declining places, the pressure on housing costs in safer areas with growth and jobs is even greater than these huge housing shortages would suggest.

The supply of homes in these places is limited. Since the ability to be secure in your home in most places takes not just the legal right to remain (citizenship or permanent residency) but property ownership, a tight housing market means fewer people are able to live there and those who rent are not able to be sure they can stay. For most Americans, access to some of the best places has already been snatched from their grasp.

This won’t change very soon. Many wealthy places are limited by their internal politics to the housing that currently exists. Indeed, their zoning and permitting processes are grounded on exclusion. They’re not interested in bringing more people in, or providing more solid renters’ rights, indeed propertied residents fight new housing tooth and nail, allowing them to realize huge unearned profits from rising home prices and housing costs — NIMBY rent-seeking. They’ve got a source of future value, and they’re going to hoard it.

There’s a gross mismatch between the supply of places that are in decent shape and the urgent demand for a lot more such places. Even for many upper-middle class people, the bottleneck is real. In fact, it’s about to get much worse.

THE SQUEEZE IS ON

We are not powerless, either individually or together. That said, triage and ruggedization will not happen everywhere it should, but rather where it can. Preparation for the future is already becoming spiky. Concentrated disruptions to remove barriers to faster action look far more likely in places that meet certain sets of conditions than in many other places. Identifying places that have natural advantages, good bones, and show a readiness to change can help us figure out where to go, and how to make a difference when we get there. But we have to choose fast.

A wave of money is washing towards these places. Durability is currently massively undervalued. Safety and good bones are undervalued. Potential to change is undervalued. The big money can read the same trends we can, once they’re aware to look for them. With decades of underbuilding, population growth, and a trend towards smaller households in larger houses, the housing shortage is already turning many North Americans into permanent renters. Even relatively modest upticks can put things out of the reach of many, and this will not be a modest uptick.

Movement is survival, but residency is security. The best way, almost everywhere, to make residency permanent is to own property. It does you no good to get to a great place, then be expelled as an outsider, or more likely, simply priced out as the rents go up. When the coming wave of money hits the ruggedization bottleneck, it’s gonna get ugly.

But major investment is moving sluggishly for now. There’s still a window in which individuals can act. Getting settled in a good place before cash tsunami comes rolling through is now, I believe, a key personal ruggedization strategy for anyone who’s not rich.

How long will that window stay open? I’ll explore this question in more depth next time, but my current guess is that in the U.S., we’re talking more than three years, but fewer than ten.

Most of us will need to find the right mix of safety, potential and affordability for the lives we seek to lead. That potential is defined mostly by a willingness to change.

We’re budget hunting for ruggedizability. We’re looking for a place to take a stand in a way that improves our lives, a home we can make safer for chaotic times, and — if you’re anything like me — a place where we can help others do the same.

In my next letter, I’ll share some strategies for finding a place to do those things.

==

-If you want to ruggedize your life, I teach classes and workshops on strategies for doing just that. You can find out more at: Alex Steffen’s Climate Courses and Workshops.

- The Guardian covered my work recently, in a piece titled, “‘All of his guns will do nothing for him’: lefty preppers are taking a different approach to doomsday.”

- Find me on Bluesky and LinkedIn.

- I’ve spoken with the media hundreds of times. I was featured in a NY Times Magazine piece, "This Isn't the California I Married." My writing was the jumping-off point for an episode of This American Life titled Unprepared for What Has Already Happened, as well as the podcasts Without; The Big Story; Everybody In the Pool and 99% Invisible’s Not Built for This series.

My podcast, When We Are, is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast and other podcast platforms around the world, or by subscribing to this newsletter.

END NOTES:

*This definition comes to us through James Barker

*Understanding the challenges facing us in our search for personal ruggedization offers some real insights into larger trends, and where opportunities in business, technology, planning and policy can be found. Being ready professionally for the demands of the future is more likely to give us the resources and leverage to take advantange of the ruggedization moves we can still make.

* The phrase is Bruce Sterling’s.