Millions Need to Relocate Away from Climate Dangers — Are We Ready?

What mass-relocation programs would take, and why you may be on your own.

Most of us are probably on our own. I find that to be the most disturbing truth about the planetary crisis.

Climate chaos and discontinuity are wracking the world around us. Even in the wealthiest nations, though, governments lack realistic plans for the large-scale relocations demanded. Currently, there’s almost no help available.

The odds are bad that we’ll act collectively at the scale demanded, in the time we have left. We’re still not even in agreement about what government-assisted mass-relocation programs should look like.

We know there’s a huge need.

Researchers estimate that millions of Americans (and 100s of millions elsewhere around the planet) will be on the move by the middle of the century, with numbers increasing as the crisis worsens. But such estimates generally factor in mostly direct impacts, and often don’t include the financial hits from exposed vulnerability, or the social costs of economic decline in brittle areas. The number of people who find themselves under pressure to move from a combination of climate risk, economic losses and social stresses could, by mid-century, be tens of millions in the U.S. alone.

National-level plans aimed to help millions relocate present enormous challenges:

The political consensus must be formed to identify risky places and fully acknowledge the scale of risk in those places. This will mean a confrontation with predatory delay interests who seek to obscure risk to continue development or preserve the inflated value of their assets.

The public must be convinced that relocation away from at least the riskiest areas is an important job for the government to take on. This will trigger a political collision with the fact of our own unreadiness. Most of us simply do not understand the changes that are unfolding all around us, and coming to that understanding will be traumatizing. There’s abundant evidence that angry denial is a common response to the experience of personal discontinuity.

The funds must be found to help those who need help. Supported relocation — where the government provides buy-outs, financial support and/or extended benefits to those who need to move — is ruinously expensive. Helping millions of people relocate could cost hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars (we don’t really know, because no one’s ever tried it at that scale). To the extent that funding was stripped out of other programs, we should expect a backlash from those losing their funding. Because assistance would be focused in certain risky constituencies and not others with different climate readiness needs (every place has climate readiness needs), other funding would need to be found for those constituencies left out in order to strike a legislative bargain. The price tag for widespread relocation is probably un-payable.

Those funds must be effectively spent, not frittered away on pork-barrel projects or community graft. This almost certainly means, among other steps, refusing the call to buy out property owners at the values their properties had before climate risk was acknowledged. The political pressures to “make people whole” are already intense. Giving into those pressures would likely doom the entire project of public support for relocation, jacking costs up to insane levels and setting in motion intense domestic political conflicts.

Relocations as part of managed retreat only achieve some important societal benefits — for example, the ability to pull infrastructure and services out of untenable communities, reducing present costs and the future need to rebuild; or the ability to turn the land under a community into a wetland or other climate hazard buffer zone — if everyone agrees to leave. In practice, this often means forcing some people to leave. This is a political minefield, even in nations with higher levels of trust and more recognition of climate realities than the U.S. I doubt it can be done at scale here, at all.

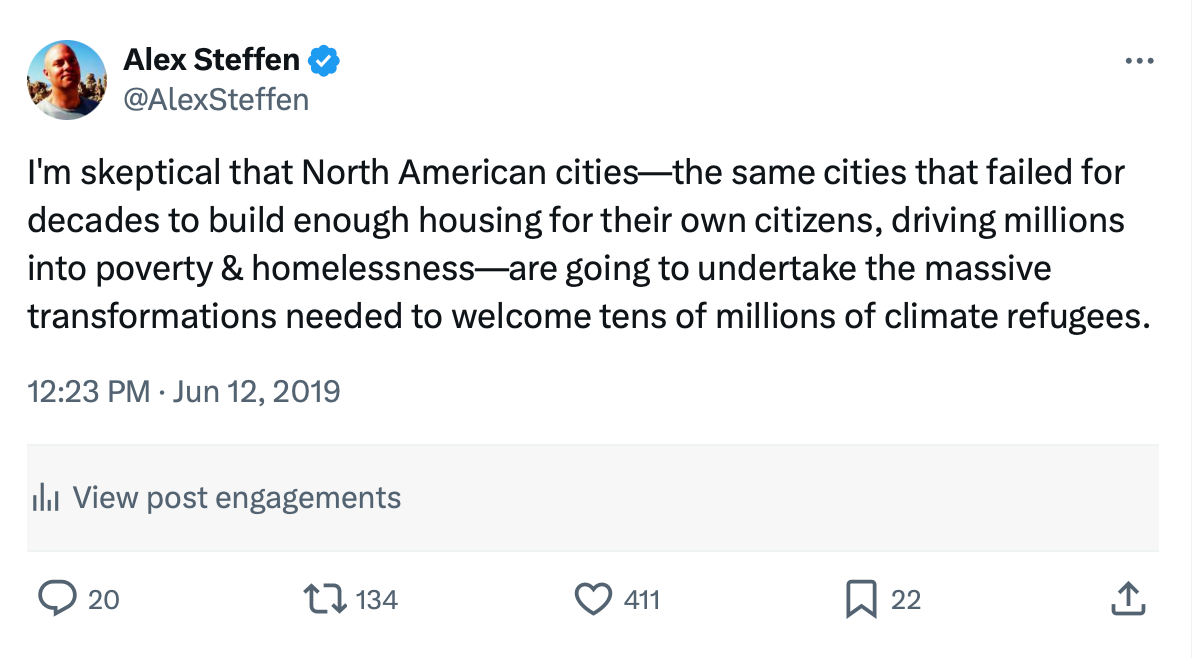

After getting people to move, you have to identify somewhere better for people to go, and support systems to help them land once they get there. The current euphemism for communities likely to be most attractive to internal migrants is “receiver cities.” These receiver cities need to be prepared to help thousands of new residents — many disadvantaged, many traumatized — to find community, find jobs, connect with social services. Not all receiver cities will be happy to end up caring for outsiders with multiple needs. Expect a backlash toward relocations and refugees, at least in some cities.

New arrivals will all need places to live. There are already not enough homes to go around. Will we build millions more, and quickly?

Meeting that scale of new housing demand in relatively safe areas is itself the pinnacle challenge. Even cities where developable land is cheaper and more abundant than in wealthy coastal areas may prove to be unable to house that many people quickly.

First, it’s obviously nowhere near certain that cities will even allow the necessary development to manage large-scale in-migration. The evidence of the last three decades suggests that most cities will simply refuse to allow that much change.

In North America, even the communities that are considered leaders in facilitating housing — for example, Spokane — generally only create welcoming conditions for a larger range of infill development (Google “missing middle”). Allowing more kinds of housing in more parts of the city is excellent, but it does not, by itself, mean more homes will exist.

The hard work of building more housing (assembling land, getting funding, permitting development, building structures and selling the resulting homes to buyers) remains unchanged. And incremental development does nothing, of course, to build the kinds of large districts that not only create lots of housing at a time, but offer a host of planning and sustainability benefits.1

Not every relatively safe place is ready to prosper, either. Some places touted as prime destinations struggle with complex, deeply-rooted problems that increased housing demand, by itself, can do little to fix. This is especially true in Rust Belt cities around the Great Lakes — like Buffalo, Detroit, Flint, Hamilton and Toledo — which often have entrenched problems of de-industrialization, financial disinvestment, corruption, multi-generational poverty, crime, addiction, racism, and pervasive toxic pollution to overcome.

It’s pretty hard to imagine how, even with currently unrealistic levels of support for people migrating away from harm, we’ll create enough housing and jobs in places for them to migrate to. That would take some of the largest, fastest building booms in history, in multiple cities around the world, starting yesterday.

I’m down to try, but let’s acknowledge what a longshot that currently looks like.

If we fail to deliver that building boom, two results seem probable:

A housing bottleneck.

Border walls.

That is, we’re almost certain to see massive appreciation in the value of properties in relatively safe places that currently function well (something I wrote about at great length in my essay The Bottleneck and You). Access to places where it is possible to build a securely prosperous life is about to be something in huge demand, with limited supply. It will be priced accordingly.2

We’re also very likely to see stronger reactions against large-scale immigration, driven by climate chaos. There’s a not-unreasonable perception that millions of new immigrants arriving in already housing-stressed, climate-impacted nations will make economic life harder for the middle-class citizens of those nations. Add that to existing culture-war xenophobic fears and identity-politics backlashes, and we’re likely to see mounting enthusiasm for closed borders.

I can’t see any way out of this mess that doesn’t start with a lot of people taking on these challenges in their own lives, on their own steam.

Obviously, if no help is coming, each of us needs to craft our own personal climate strategies. If you can’t count on the government to make sure you get to a good place to put down roots as the planetary crisis worsens, you’d better figure out how to do it yourself.

But we also need more people demonstrating their engagement with what science and foresight tell us about the near future. Denial and delay are the biggest obstacles we face, because we can’t even begin to tackle the logistics of moving millions to safer ground while we continue to ignore the crisis. People engaging in personal ruggedization demonstrate their own seriousness — and for almost everyone, personal commitment is the most persuasive argument.

Be persuasive.3

It’s also worth remembering that there are physical limitations to the volume of construction a given place can undertake, given the conditions it begins with. There are only so many large cranes to rent, or skilled plumbers to employ. The capacity to build doesn’t magically spring up to match demand.

Climate migration, of course, has already begun, and some relatively safe places have already seen steeper-than-average increases in home prices and rents. We’re still early in the curve, though. My sense is that the biggest wave of appreciation in these places is still 3-to-5 years out.

I have a lot more to say about this topic, about how a small wave of climate-rugged individuals taking open action could help drive a larger wave of climate response, but I’ll save that for another letter.