Dispatches from an Unready World

Four perspectives on the Brittleness Bubble and our future.

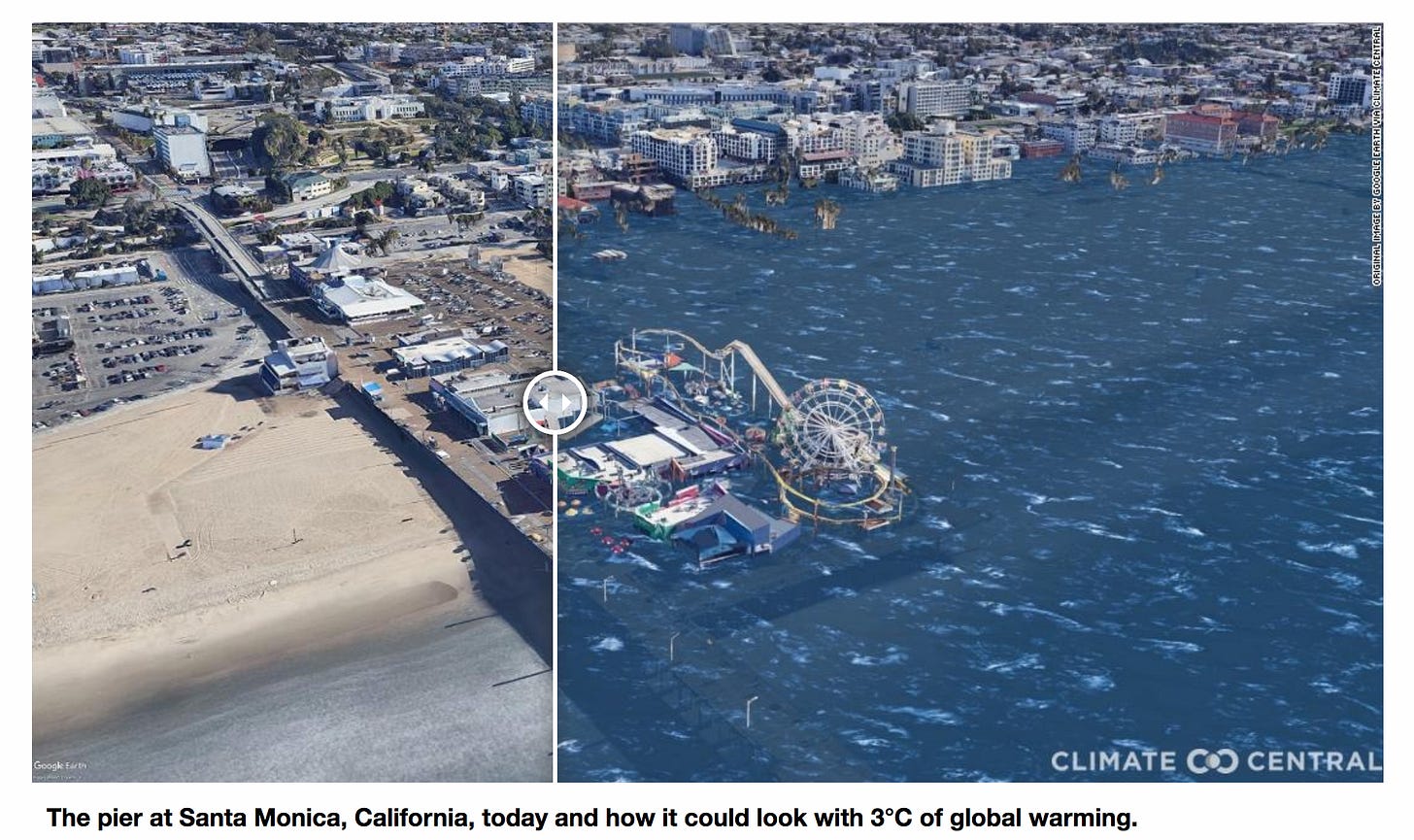

What will future sea level rise look like?

That’s the question these Climate Central images attempt to answer. They take Google Earth images of famous spots from around the world (like the Santa Monica Pier) and then create slider-bar pictures of the same location submerged beneath the rising waters.

Of course the seas are rising, and it helps to visualize what that means: visualization and anticipation are closely linked. But this is not what low-lying places will look like in the future, no matter what emissions pathway we end up on. In fact, these sort of images distort as much as they reveal.

Sea level rise will not occur in an otherwise unchanged world, but will instead drive huge changes as it comes and as it combines with a whole wave of other major shifts in the climate and biosphere and their impacts. Those shifts, in turn, are already accelerating powerful societal forces which are themselves major drivers of change. The water will come, but it won’t arrive at the world we’re still pretending we live in today.

Back in the day, I used to talk about how the central conceit of most canonical zombie films is that time stops the minute the undead rise: no new technologies are introduced, environmental problems drop into the deep background, society usually changes only through regression into tribes of survivor groups, and so on. The zombie apocalypse ends progress. Everything stays as it is, and just continues to fall apart.

In a weird way, many of our images of planetary disasters also freeze the future, when, in reality, the planetary crisis has already launched us into decades of rapid and disruptive changes in human societies, whether we choose that outcome or not.

This is true even in the places that are culturally most resistant to acknowledging planetary reality.

In this New York Times piece, As Manchin Blocks Climate Plan, His State Can’t Hold Back Floods, Christopher Flavelle (who for my money is one of the best climate adaptation reporters in America) covers the bitter truth that even while West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin guts President Biden’s climate plan for the benefit of his friends in Big Coal, his own state is among the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. And, “when it comes to climate, there’s also an economic toll from inaction.”

“‘The geography and topography of the state results in many homes, roads and pieces of critical infrastructure being built along rivers, around which we show extensive flooding…’ But topography isn’t all that raises West Virginia’s flood risk. Surface mining for coal has removed soil and vegetation that once absorbed rain before it reached creeks and rivers, and has pushed rocks and dirt into those waterways, making them less able to contain large volumes of water.”

It is critical to remember, as well, that none of these analyses of risk take the crisis seriously enough, because every place confronts multiple overlapping risks, some only measured and modeled with difficulty, some currently beyond our capacity to predict. As we’ve discussed before, the reality of discontinuity itself — and the loss of predictability it brings — is the single greatest cost of this crisis.

Most West Virginians have, like most people everywhere, a large and pressing self-interest in accelerating action on climate and sustainability, ruggedizing in the face of catastrophic risks, and building systems of governance that know what they’re doing in this discontinuity. They also have a politics guaranteed not to deliver any of that.

There’s also this fine piece in the Atlantic, When the Place You Live Becomes Unlivable, about the ties of love and identity and community that bind people to places, even as they recognize the brittleness of their surroundings.

One of the costs of predatory delay blocking the recognition the magnitude of the impacts we all face (and the speed with which they’re coming) is that a huge number of people don’t have any idea how to make wise decisions about whether and where to go, and how to build a life.

“Each time a big hurricane hits, many coastal residents move away, permanently escaping our region’s cycle of destruction and rebuilding. But the choice to leaved is far from easy. Hurricane season is fickle; some years the storms skirt the state entirely, other years they pummel our coast over and over again. Such unpredictability presents a conundrum for inhabitants of Gulf states. How do you weigh the various costs of leaving—financial, cultural, and emotional—against an uncertain future? For many, the scale teeters more than tips, the decision as clouded as a thundering sky.”

In the absense of insight or guidance into how to ruggedize their lives and communities — and faced often with a lack of resources to act even if they knew what to do — many people hunker down and hope for the best, living to enjoy the world and the weather they have, while it lasts.

Which brings me around to the opera “Sun & Sea,” which is reviewed here by Mark Swed:

“Sun & Sea.” The Lithuanian installation opera proved a sensation at the Venice Biennale two years ago and is now finishing up an American tour at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Geffen Contemporary. It is an opera for a few. An hour long, it is given five times a night, accommodating an audience of only 102 for each performance. The $25 tickets for the 15 performances Thursday though Saturday sold out in minutes. Funnily, a work about the horrors of global heating is said to be the hottest ticket in town.

In the end, what makes “Sun & Sea” horrifying is that a leisurely day at the beach is depicted not with the terrors of climate change but with the ostensible lack of them. It is an opera about caring but not doing, about environmental ennui, which just may turn out to be our biggest threat of all…

These beachgoers know that the sand in Santa Monica will be gone and the pier underwater due to rising sea levels. The grandchildren of the children on the beach may very well have no beach.

We’re all on that beach, and the wind is picking up, and it’s getting harder and harder to ignore the voices asking, “When would be the right time to leave? Where would we go? Who would we try to be when we got there?”

I have a lot more to say on these matters in the Snap Forward book, about which I’ll soon have exciting news to share. So please stay tuned.

Yours on hot sand,

Alex

P.S.: Do you know someone who’d be interested in these ideas? Please let them know about this newsletter.

P.P.S.: Also, supporters get access to my podcasts, which will resume streaming this week. If you would like to hear more, and help me do this work, please consider subscribing.