Unpatterning

What comes next is not a new version of what came before.

Our thinking is changing far less quickly than our circumstances.

We live amidst discontinuities — unprecedented situations for which our past expertise and experience offer us poor guidance — yet we cling desperately to the mental habits of continuity. Even when we discuss vast transformations, we map them to our understanding of how the world used to work.

Case in point: what grows where.

Not long ago, the United State Department of Agriculture (USDA) released an updated Plant Hardiness Zone Map.

This tool helps farmers and gardeners understand the average temperature ranges in the places they live, thus helping them plant crops that are likely to thrive. Since the planet is heating, temperature ranges are shifting, and the USDA updated their map to reflect this fact.

We have set ourselves up to be fooled here, though. Many people will fall into the understandable trap of believing that this map is analogous to previous heartiness maps, that this map reflects our “new normal.”

We think things like: if some fields in the chilly Northwestern Palouse used to be 6a and they’re now 7a, that must mean that new crops are a better bet there. Let’s put in some vineyards!

But the new hardiness zones are not the old hardiness zones. They are not an update of a continuous past into a new-yet-also-continuous present. They’re not a description of a new normal. They’re a symptom of something very different indeed.

That’s because climate chaos and ecological collapse do not change the world around us in linear, simple ways. The weather doesn’t just get a little warmer, or a little wetter, or a little more hospitable to a different group of migratory songbirds. It gets weirder, too. It gets unstable. It gets dangerous.

Extreme temperatures grow far more likely, with more disastrous effects. So yes, the Northwest is warming on average, but it also had a completely unprecedented heat wave in 2021, followed by an unusually severe ice storm this winter that brought down power lines, barn roofs and thousands of old trees.

Biological shifts are also a two-edged blade. The warmer weather may be extending the growing season, but it is also facilitating the spread of crop rusts and fungi, and making life easier for invasive crop pests, like the brown marmorated stink bug. Unforeseen ecological consequences ripple outwards from every shift.

And, of course, changing temperatures are not the only prerequisite for a successful crop. New plants may need particular soils and nutrients, new pollinators, or even demand light or humidity that increases on the seasonal schedule of a different latitude. A plant can be climatically suited to a place and still fail for other reasons.

Finally, these zones themselves are a moving target, almost certain to keep changing as the world warms. Trees we plant today, for instance, have to survive all this present variation and also thrive in whatever temperature ranges and ecological conditions their place will experience in coming decades. And those changes, in turn, may happen in ways that are sudden and highly discontinuous from what we think we know about farming or gardening in a given place.

Now, the USDA itself is quite careful to explain that hardiness zones are only the most general of guides, and that relying too heavily on them can have disastrous results:

“Zones… are based on 1991-2020 weather data. This does not represent the coldest it has ever been or ever will be in an area, but it simply is the average lowest winter temperatures for a given location for this 30-year span. Consequently, growing plants at the extreme range of the coldest zone where they are adapted means that they could experience a year with a rare, extreme cold snap that lasts just a day or two, and plants that have thrived happily for several years could be lost. Gardeners need to keep that in mind and understand that past weather records cannot provide a guaranteed forecast for future variations in weather.”

But most people don’t read the fine print.

Instead, I see repeated efforts to shoehorn discontinuous change into the framework of continuity.

Take, for instance, this Atlantic piece, “Too Few Americans Are Eating a Remarkable Fruit,” whose subhead tells us confidently that “breadfruit is a staple in tropical places—and climate change is pushing its range north.”

The premise of the piece, you might have gathered, is that breadfruit is awesome (true), only thrives in hot places (true), and that global heating is about to make parts of the U.S. a lot hotter (true, on average) and these newly hot places will be perfect for growing breadfruit (it’s complicated).

Writer Zoë Schlanger is properly measured in the article itself, noting that while rising temperatures do potentially push the breadfruit’s range northwards, “a couple days of 40-degree (F) temperatures would kill one,” that even “Florida does get an occasional cold snap,” and that “Breadfruit might just be another commodity tossed about by freak weather.”

But most readers, I’ll bet, miss the caveats and jump straight to the conclusion that breadfruit is a novel part of the new American continuity. America, as we knew it, but with fewer ski-slopes and more breadfruit fritters.

That’s because we are conditioned to believe the myth of a return to normal, of an altered but sustained continuity (or, failing that, of an all-encompassing apocalypse), and that myth renders us blind to the reality around us. As I wrote before:

We have all been raised to expect that when things change from a pattern we’re used to, they eventually settle in to a new pattern we can learn to live with, a new normal. This expectation has largely been true in the past: things change, baselines shift, the young grow up used to it, eventually no one notices. No longer.

To put it another way, we are hungry to be told that if recent patterns of life have unraveled, that they’ll be replaced by a new pattern, and that our job is just to wait for someone to explain to us how the new pattern works.

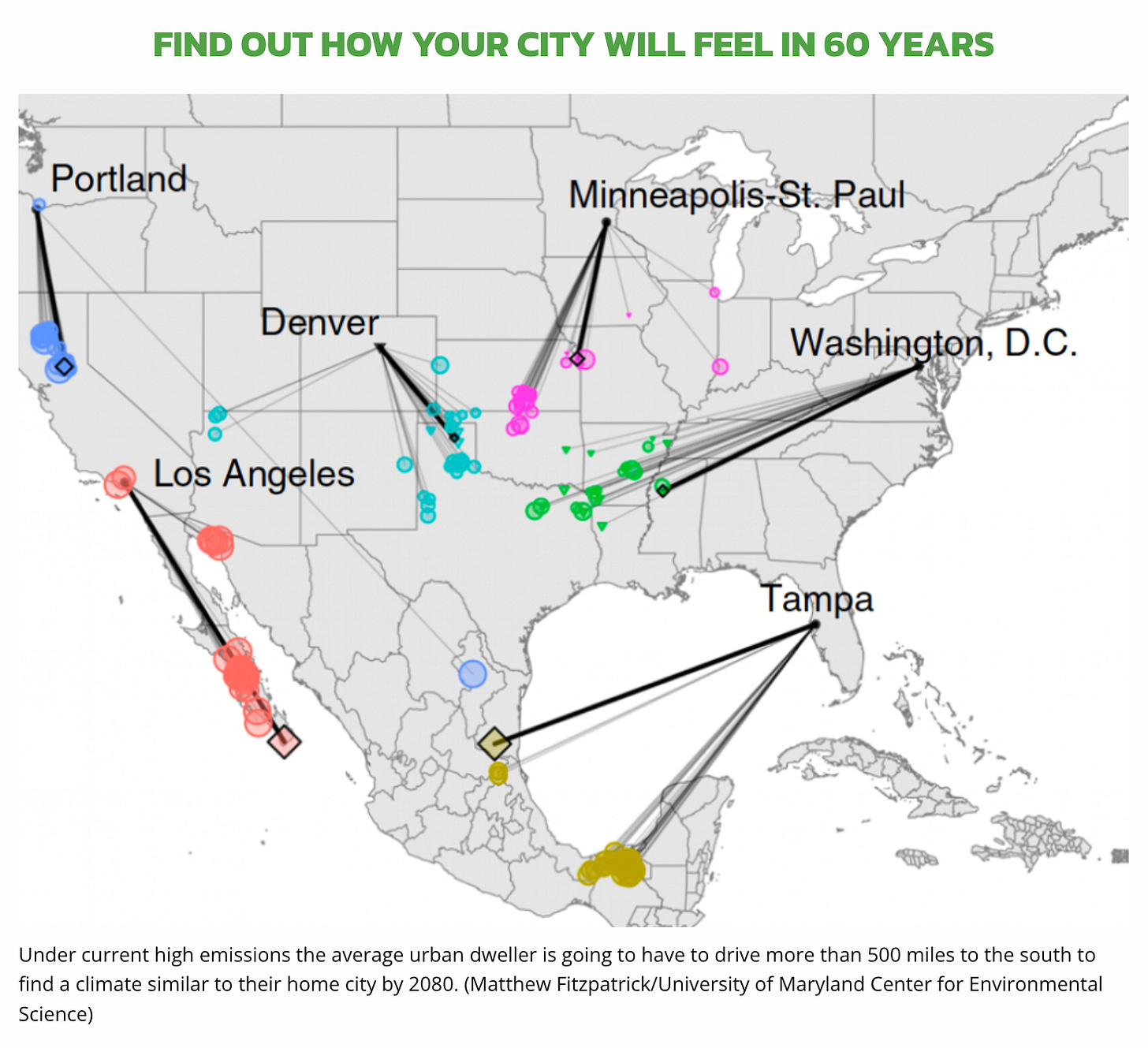

Consider, for instance, this provocative mapping project from a few years back.

The idea is that one can get a prediction of the future climate of a city in the form of a comparison to the climate of a city today. For instance, in six decades Eugene may find itself with a climate that is (on average) similar to the climate of Paradise, California now.

The danger here comes in believing that having a similarity in average climates means a clean and continuous switch from like to like: Eugene turning into Paradise.

The reality is far messier: a jagged path from one general experience of temperature and precipitation to another — with resulting weather patterns, and climate impacts and ecological shifts that aren’t likely to be very stable, much less final. Again, the work itself contains appropriate caveats, but the nature of the visual inclines us to think of this as a description of the new pattern we’ll get as our old and established pattern changes.

The truth, of course, is that what comes after the old patterns is something different altogether: an unpatterning.

An unpatterning involves somewhat stable interconnected systems, fraying apart in ways vast and small, sudden and slow, obvious and semi-undetectable; coming together in previously unseen arrangements; then unpredictably fraying again, assembling in new temporary conditions and unstable states, again and again. Not every change will be a huge catastrophe, but every change will be felt, and the aggregate effect of all this change will be to break our sense of how things work.

This impermanence unseats our sense of ecological balance and our deep ties to place. It renders our old ideas of sustainability and an orderly transition out of alignment with the actual world. It demands ruggedization against the fact of unrelenting change itself. The worse we let the crisis grow, the more ruinously expensive this tornado of unpatterning will get.

We can limit the magnitude of the crisis driving discontinuity. Once unleashed, though, discontinuity is not a problem we can solve. It is the context in which we solve problems.

In the meantime, we’ll have weird weather roiling the skies above us, and strange flowers blooming in the garden, and distant rumors of breadfruit pudding.

PS: I’ll be teaching a quick introduction to personal ruggedization on April 25, 2024, from 10:00 a.m. to noon, Pacific Time. Save the date: sign up information in the next email!

How to find me elsewhere online:

- Schedule a consultation with me to discuss personal ruggedization in your life or business, or to explore a business opportunity.

- Want me to give a keynote talk at your conference, or a bespoke presentation for your meeting? Email to inquire.

- Subscribers to this newsletter also get first notice about online classes (with subscriber-only discounts).

- Check out my books: Worldchanging and Carbon Zero

- View my TED Global talks on sustainability and cities.

- I was featured in a 2022 NY Times Magazine piece, "This Isn't the California I Married," and my writing was the jumping-off point for an episode of This American Life: Unprepared for What Has Already Happened.

- I’ve recently talked about ruggedization and sustainability on these podcasts: Without; The Big Story; Everybody In the Pool.

- Visit my Bookshop shop to discover some of my top reads.

- Stay connected on social: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky